The energy sector is a major contributor to the government’s taxation revenue stream. Over time, the energy sector’s contribution as a percentage of the total has been falling due to declining production and volatility in international pricing. Nevertheless, the sector is the highest taxed sector in the T&T economy. In fact, operations of upstream companies result in over 30 different taxes, levies, and fees. The ones that are unique to the sector are the Petroleum Profit Tax (PPT), Supplemental Petroleum Tax (SPT), and Royalties. Companies engaged in upstream operations in Trinidad and Tobago (T&T) are subject to a special fiscal regime, principally governed by the Petroleum Taxes Act (PTA).

The primary tax paid is the PPT. This is 50% of taxable profits, whereas other companies in the country pay 30–35% corporation tax. SPT is chargeable on the gross income (derived from the sale of crude oil) less royalties and overriding royalties paid on the crude oil sold. The tax is computed separately in respect of land and marine operations and is a quarterly tax based on the actual gross income for each quarter. In Trinidad and Tobago, the royalty tax on energy producers is a flat rate of 12.5% of the total quarterly revenue for crude oil, condensate, and natural gas. This tax is also based on production volume rather than profit.

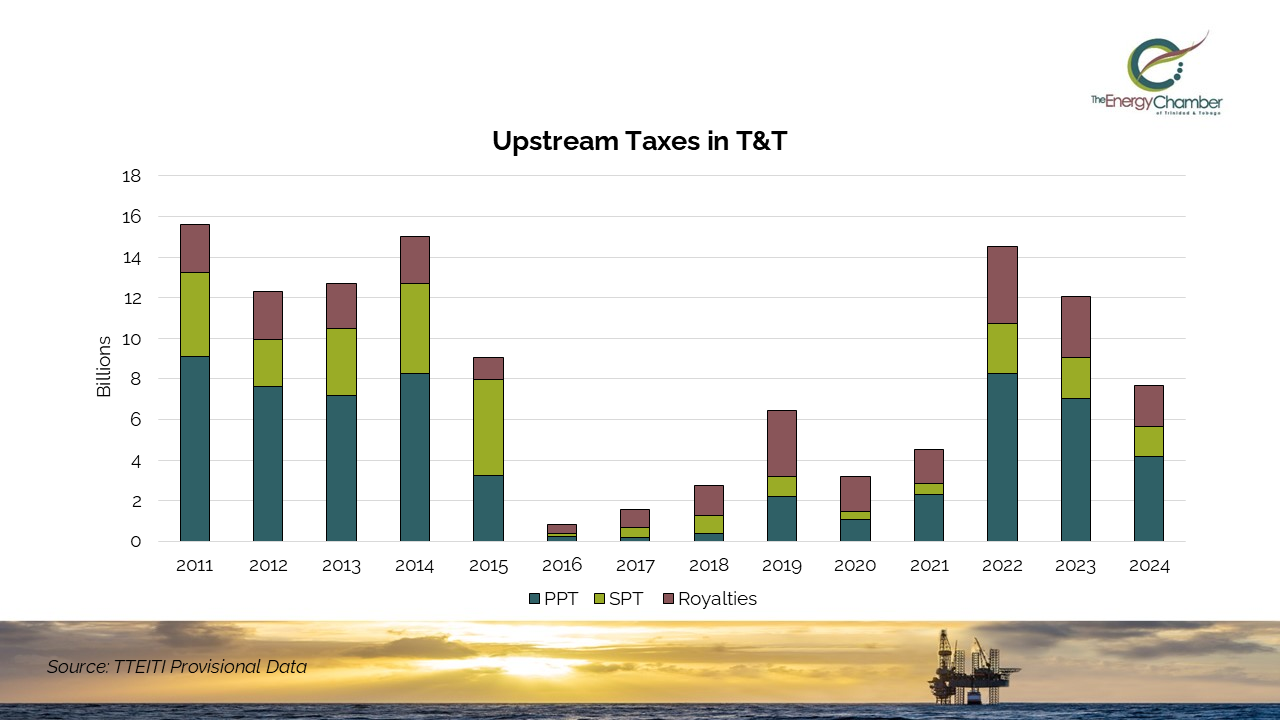

These three taxes make up the majority of the taxes earned by the government from the energy sector. PPT, on average over the past 10 years, made up about 43% of the taxes paid each year by the upstream companies. SPT accounted for about 23%, and Royalties were about 33%.

In 2015, there was a major shock to the energy sector with booming shale oil production, which caused a glut in the market that drove prices down. This resulted in profitability in the energy sector falling dramatically; this was a major contributor to the fall in revenue from the sector in 2015 and 2016. In addition, several major upstream companies benefitted from the application of capital allowances during this period, which reduced PPT.

Historically, royalty payments were made by crude oil producers. This, however, was changed in 2017 when royalties were applied to natural gas producers as well. This, along with price recovery, aided in stabilizing the tax collection from the energy sector. During the period 2015 to 2020, PPT payments fell, for the first time, below 50% of the total tax collected from these three items. It fell to as low as 12% in 2017. At this time, royalty payments played a more important role in the tax structure during those years.

SPT is a tax measure that we discussed in previous articles. SPT was introduced as a windfall tax in the 1980s to enable the Government to share in the windfall revenues accruing from spikes in the international oil price, but today it no longer operates in that vein, representing simply a further tax charge on the income of upstream producers. It also has a direct impact on the commerciality of an upstream project in a licensed area.

Today, the tax does not serve the purpose for which it was originally intended since price and cost structures have changed substantially since the 1980s. It does, however, now contribute to around 23% of the tax from the sector.

While these taxes contribute substantially to the government’s revenue and are a benefit to the nation, they create an issue for upstream producers to re-invest into capital projects in the country, since margins are squeezed tightly. These taxes, along with other tax challenges like VAT refunds owed to the major oil and gas producers, create significant problems. The VAT refunds owed to individual companies are in excess of the cost of drilling new wells.

Drilling an onshore well costs between $1.5 million and $5 million, and an offshore well costs in excess of $50 million. An onshore producer has indicated to the Energy Chamber that three (3) wells could be drilled with the VAT refund owed to the company.

The challenge in T&T is that it is a mature oil and gas producer and does not offer attractive propositions when it comes to investment. Other countries with more exciting and attractive subsurface potential are seeing increased inflows of capital. Often, these new energy jurisdictions also offer more competitive fiscal and commercial terms, which makes it easier to attract investments.

Future investments are critically needed at this juncture in T&T. As we alluded to in the previous article, production is still falling, and growth of production is unlikely to materialize in the short term, so the impetus must be to stabilize domestic production. The Energy Chamber maintains its position that while cross-border gas creates an exciting value proposition in the short term, it needs to be done at the same time as creating a better fiscal environment for improving future domestic production.